This article was originally published in the Jan./Feb. 2016 issue of West Virginia Focus magazine.

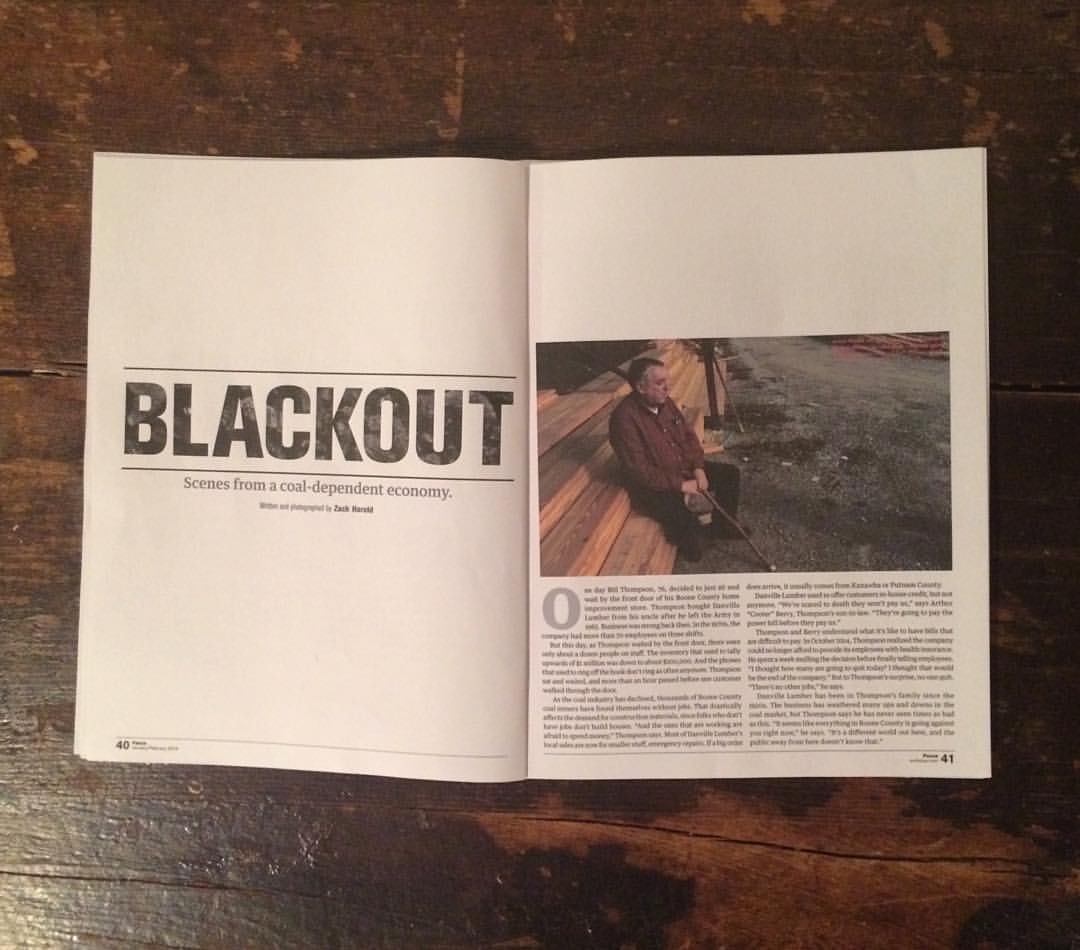

One day Bill Thompson, 76, decided to just sit and wait by the front door of his Boone County home improvement store. Thompson bought Danville Lumber from his uncle after he left the Army in 1963. Business was strong back then. In the 1970s, the company had more than 70 employees on three shifts.

But this day, as Thompson waited by the front door, there were only about a dozen people on staff. The inventory that used to tally upwards of $1 million was down to about $200,000. And the phones that used to ring off the hook don’t ring as often anymore. Thompson sat and waited, and more than an hour passed before one customer walked through the door.

As the coal industry has declined, thousands of Boone County coal miners have found themselves without jobs. That drastically affects the demand for construction materials—folks who don’t have jobs don’t build houses. “And the ones that are working are afraid to spend money,” Thompson says. Most of Danville Lumber’s local sales are now for smaller stuff, emergency repairs. If a big order does arrive, it usually comes from Kanawha or Putnam County.

Danville Lumber used to offer customers in-house credit, but not anymore. “We’re scared to death they won’t pay us,” says Arthur “Cooter” Berry, Thompson’s son-in-law. “They’re going to pay the power bill before they pay us.”

Thompson and Berry understand what it’s like to have bills that are difficult to pay. In October 2014, Thompson realized the company could no longer afford to provide its employees with health insurance. He spent a week mulling the decision before finally telling employees. “I thought how many are going to quit today? I thought that would be the end of the company.” But to Thompson’s surprise, no one quit. “There’s no other jobs,” he says.

Danville Lumber has been in Thompson’s family since the 1920s. The business has weathered many ups and downs in the coal market, but Thompson says he has never seen times as bad as this. “It seems like everything in Boone County is going against you right now,” he says. “It’s a different world out here, and the public away from here doesn’t know that.”

* * *

Recent declines in the coal industry are wreaking havoc on West Virginia’s economy, especially in the southern part of the state.

The state produced 166 million short tons of coal in 2008, according to data compiled by the West Virginia Coal Association. By the end of 2014, production was down to around 117 million. The state has also seen massive layoffs during that time. In 2009, there were nearly 28,000 people working in mining jobs. That has fallen by 65 percent, with just 18,000 coal mine employees in 2014.

The slide in production and jobs can be attributed to four main factors: the ever-growing difficulty of mining coal in southern West Virginia, competition from cheap natural gas, tougher carbon emissions standards from the federal government, and a weak international export market.

These factors have been studied by economists and geologists and debated by politicians and lawyers, as they should be. But something that is often lost in those high-level conversations is the very real effect these declines have had in small communities all across West Virginia.

And nowhere has been more affected than Boone County.

* * *

In some ways West Virginia owes its coal industry to Boone County. It was here that, in 1742, European explorer John Peter Salley was exploring a tributary of the Kanawha River when he noticed a thick black seam running through the rocks along the river. Salley would dub the waterway “Coal River,” a name it still bears today.

Just like West Virginia as a whole, Boone County has based almost its entire economy on coal mining for a very long time. And for a very long time this made perfect sense because Boone County produced vastly more coal than anywhere else in the state. In 2008, the county mined 30.9 million short tons of coal. Its closest competitor, Mingo County, produced 11.9 million short tons that year.

As a result, the county government received lots and lots of money from coal severance taxes. In 2010 alone, Boone County received $5.3 million in severance taxes. The county commission used this money in myriad ways—including hiring college students for summer jobs at the courthouse, stocking rivers and streams with catfish and trout, paying for public transportation, and funding construction projects on county offices and parks.

But over the last few years coal severance monies have steadily declined, forcing the county to cut back. County Commissioner Mickey Brown says the summer job program ended around 2012. The county stopped stocking fish in 2014. In 2015, the commission dropped funding for public transportation and cut its contributions to local municipalities, the county health department, and the county parks and recreation department by 30 percent.

On January 30, 2016, the county will close its public dump, where many Boone County residents dispose of their household trash for free. The program cost about $1.2 million per year and was paid for entirely by coal severance taxes. Commissioners are also looking at ways to bring down the county’s $1 million jail bill using less expensive sentencing options like day report centers, home confinement, and drug court. Brown estimates this will save the county about $150,000. “We knew things were going down but we didn’t know how drastic it was going to be,” he says.

* * *

The lights are off in the front room of Bill Stone’s office in Danville. He sits behind the receptionist’s desk with a large cup of coffee and some store-bought muffins. He has Fox News on a small television screen but the sound is turned off.

Stone, 77, is dressed in hiking boots, pressed chinos, and a denim shirt with his company’s name embroidered on the left lapel: J&R Cable. He started working here in 1980 and bought the business from its original owners, J.R. Roger and Larry Javins, three years later. He never bothered to change the name, or even add his own initial. There wasn’t time.

The business provides industrial-grade cables to underground and surface mining operations. Since mines use a lot of power, they need a lot of heavy-duty cables. In the good years—basically anytime before 2008—J & R Cable serviced between 50 and 60 mines in a 150-mile radius from its Boone County headquarters. Now the company has about 10 clients.

At one time Stone employed 17 workers. Now there are just eight people, including him. As business has dried up, Stone has been forced to cut back on overtime. Three years ago, he cut his employees back to four days a week. That’s why the office is dark—his office staff is out on Fridays.

Stone says there isn’t any way to pivot the business, to find new clients for the service he offers. A few times a year he might get a call from a gravel pit or cement company, but those businesses don’t need nearly as much cabling as the mines.

Nearing his eighth decade, Stone would like to retire in the next few years. But even quitting might be difficult. “I don’t think this business will ever sell. It’s not feasible or practical.” He imagines the company will have to be liquidated, sold off piece by piece. He jokes he’ll turn the property into a bed and breakfast. “There’s no light at the end of the tunnel. They’ll be mining coal, but it won’t be like anything we’ve seen in the past.”

* * *

In a small cinderblock gymnasium, under humming lights, a crowd of about 90 people sat on folding chairs and plywood bleachers waiting for a meeting to begin. Members of the Boone County Board of Education and school system administrators sat at a long table at the front on the room.

Off to the side was a large projection screen showing a PowerPoint presentation with an unwieldy title: “Reasons and Supporting Data Required for the Closure of Nellis Elementary school and the Consolidation of Nellis Elementary with Ashford-Rumble Elementary.”

Boone County Schools had three of these meetings in fall 2015, one for each of the three elementary schools that will permanently close once this school year ends. It’s not uncommon for counties to close schools but usually when that happens students are moved into larger, newer, nicer schools. Not here. Students at the three closing schools will just be sent to three other small elementary schools.

It’s a drastic cost-saving maneuver, but a necessary one when you look at the school system’s budget. The county’s student population fell from 4,599 in the 2013-14 school year to 4,331 in 2014-15, leading to a $1.2 million cut in state Department of Education funding. Then in October, Governor Earl Ray Tomblin called for a 1 percent cut in state aid to schools. That cost Boone County $176,000.

But worst of all, the county’s property tax income has taken a major hit. Collections fell by $2.2 million between the 2014 and 2015 budget years. During the first four months of the 2016 budget year, property tax revenue was $4.8 million lower than it was the year before.

The school system had only one option to make up the shortfall—deep budget cuts. “We tried our best not to touch our schools,” Superintendent John Hudson says. The school board cut operation costs, eliminated 37 positions in middle and high schools, as well as five positions at the central office. That amounted to $2.6 million, but it wasn’t enough.

Closing the elementary schools is expected to save around $1.8 million. Hudson figures he will have to find an additional $1.6 million in cuts just to balance next year’s budget. “People say, ‘Do something else.’ Well, what is the something else?” he says.

All West Virginia schools receive money from the state Department of Education according to the size of their student populations. Many counties supplement that income using property taxes, collected through regular and excess levies. For a long time schools in the southern part of the state greatly benefited from these levies, because they were able to collect property taxes from coal mining operations.

During the industry’s salad days, Boone County Schools were able to hire as many as 130 more employees than state education funding allowed, based on that property tax money alone. “We had that luxury,” Hudson says.

Now things are heading in the opposite direction. “When you see companies going out of business, that affects our tax collections,” Hudson says. He sees the evidence every time he leaves his Madison office and drives on West Virginia Route 85 toward Van High School, or State Route 3 toward Sherman High School in Seth—big pieces of machinery being hauled away on the backs of trucks. With each one that crosses the county line, Boone County Schools loses a little more money.

The economic realities of the situation provided little comfort to the parents, teachers, and community members for at the consolidation meeting at Nellis Elementary, however. Some parents begged—and some demanded—board members find other ways to save money. “Give yourself a pay cut,” said Sandra Evans, whose grown children once attended Nellis.

Robert Blaylock, a parent, suggested cutting one of the system’s two assistant superintendents. “You’re taking the heart plumb out of this community,” he said. Kim Lay, who has taught at Nellis for 10 years, asked if the board was going to let “the almighty dollar” cloud their judgment. “Cuts need to start from the top. Not our children. Not our future.”

* * *

Christina Adams spent more than 20 years in the classroom, including 10 years teaching kindergarten, before she became principal of Wharton Elementary three years ago. “I just felt like I was ready for that challenge,” she says. “I wanted to make a difference. A big picture difference.” She says she cried for a week when she found out Wharton would soon close its doors for good.

With three fewer schools to staff, Boone County will likely lay off many teachers and service workers, although it’s still unclear how many layoffs will be necessary. Adams will have a job next year—she has over 25 years seniority with the school system—but it’s doubtful she will be able to find another principal position. “Change is good because it keeps you on your toes, but I haven’t got comfortable enough in this job to be ready for that change yet,” she says.

It hasn’t been an easy couple years for Adams’ family. Her husband worked for Patriot Coal and was laid off for three months in 2014 before going back to work for about a year. He was laid off again in March 2015. “We saw the handwriting on the wall and decided we’ve got to have a plan B,” Adams says.

Her husband had been making extra money by running heavy machinery. He decided in July 2015 to make that his full-time job. Business is doing “fairly well,” Adams says, but she doesn’t know what will happen if the venture doesn’t work out. “There’s no plan C. Plan C might be to move out of state—although that’s not what we want to do.”

Adams has seen many families in her school face similar decisions. When she first took the job, Wharton had 124 students. Now the school has 96. “A lot of them, parents come in and say we’re leaving the area. I’m going out west, I’ve got a job, I’m taking my family and going.”

* * *

It is easy, with the benefit of hindsight, to pinpoint ways Boone County might have avoided its current financial turmoil. The school system could have consolidated some of its elementary schools years ago to avoid having to shutter three schools at once. The county commission could have depended less on coal severance money to fund services. Leaders could have put more emphasis on diversifying the economy, creating more opportunities at home for young people.

But it’s also easy to see why none of those things occurred. “We were so spoiled by coal and what it was doing for us we were never able to bring in another industry,” says Bill Stone at J & R Cable.

There are a few reasons to be hopeful about the coal business. “Some doomsday people are saying coal is going to go to zero. That is absolutely not true,” says John Deskins, director of West Virginia University’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

Deskins’ office released a report last year predicting coal production will drop to 98 million short tons in 2016 but rise to about 105 million tons in 2020. Rising natural gas prices, a continued demand for coal in the steel industry, and a healthy international export market will fuel this resurgence, Deskins and his team believe.

But what happens from there? In the worst-case scenario, annual production could fall to 80 million short tons by 2035 if the government imposes strict carbon-cutting environmental regulations, Deskins says.

In the best-case scenario, a growing global economy will drive up the demand for both steel and coal.

This will not be enough to completely revive the industry, however. “We don’t expect anything like we saw even a decade ago,” Deskins says. “Best case scenario, coal may go back to 110 or 115 million (short tons per year), and that’s still a big drop.”

Which scenario is more likely? It doesn’t really matter. Even in the most optimistic future, West Virginia’s coal production will still only be a fraction of its heyday. Which means, at least for the foreseeable future, the people of Boone County and the rest of southern West Virginia will continue to face some very difficult choices.

* * *

About a month before their ninth wedding anniversary in October 2015, Brittany and Derek Chase packed up their three children in the family minivan and made the ten-hour drive from their home in Boone County to an apartment in Bristol, Connecticut. They stayed there for two months before moving again, this time to Hazelton, Pennsylvania. They will probably move again in a couple more months—Brittany hopes to somewhere warmer.

The Chase family has adopted this nomadic lifestyle because of Brittany’s new job. She is a travel nurse, transferring between hospitals every few months, wherever there’s a shortage of help. It’s a career move she has wanted to make for a long time but Derek was always hesitant. “We’d talked about it before but we didn’t do it. I still had a job and I didn’t want to pick up and move,” he says.

His hesitation waned once his employer Patriot Coal declared bankruptcy. Sensing layoffs in the near future, Derek applied for a job with CSX. He got the job, but the railroad kept pushing back his training—first it was scheduled to begin in July, then August or September, and then it was canceled altogether. CSX is having financial difficulties of its own, partially because of the lack of coal being shipped on the rails.

The family decided it was time for a change. Brittany hired on with a travel nursing agency and they headed for New England. It was excellent timing. Just two months after they arrived, Patriot laid off 1,900 workers in Boone and Kanawha counties, including Derek’s former coworkers.

Their new life in New England has been an adjustment. Brittany is now the family’s sole breadwinner. Instead of going off to work, Derek now spends his days homeschooling the kids while trying to finish his bachelor’s degree online through Marshall University.

Their children—Rylee Jo, 2, five-year-old Jackson, 5, and Brooklyn, 7—are adjusting well, making new friends in each new place. “They think it’s the best thing ever,” Brittany says. But after the family returned from a trip back to West Virginia for Thanksgiving, they started asking why they couldn’t go “home.”

For Brittany, missing home is mostly about missing her mom. “Every time I talk on the phone with her, she cries,” she says. “I feel like I’ve broken my mom’s heart.”